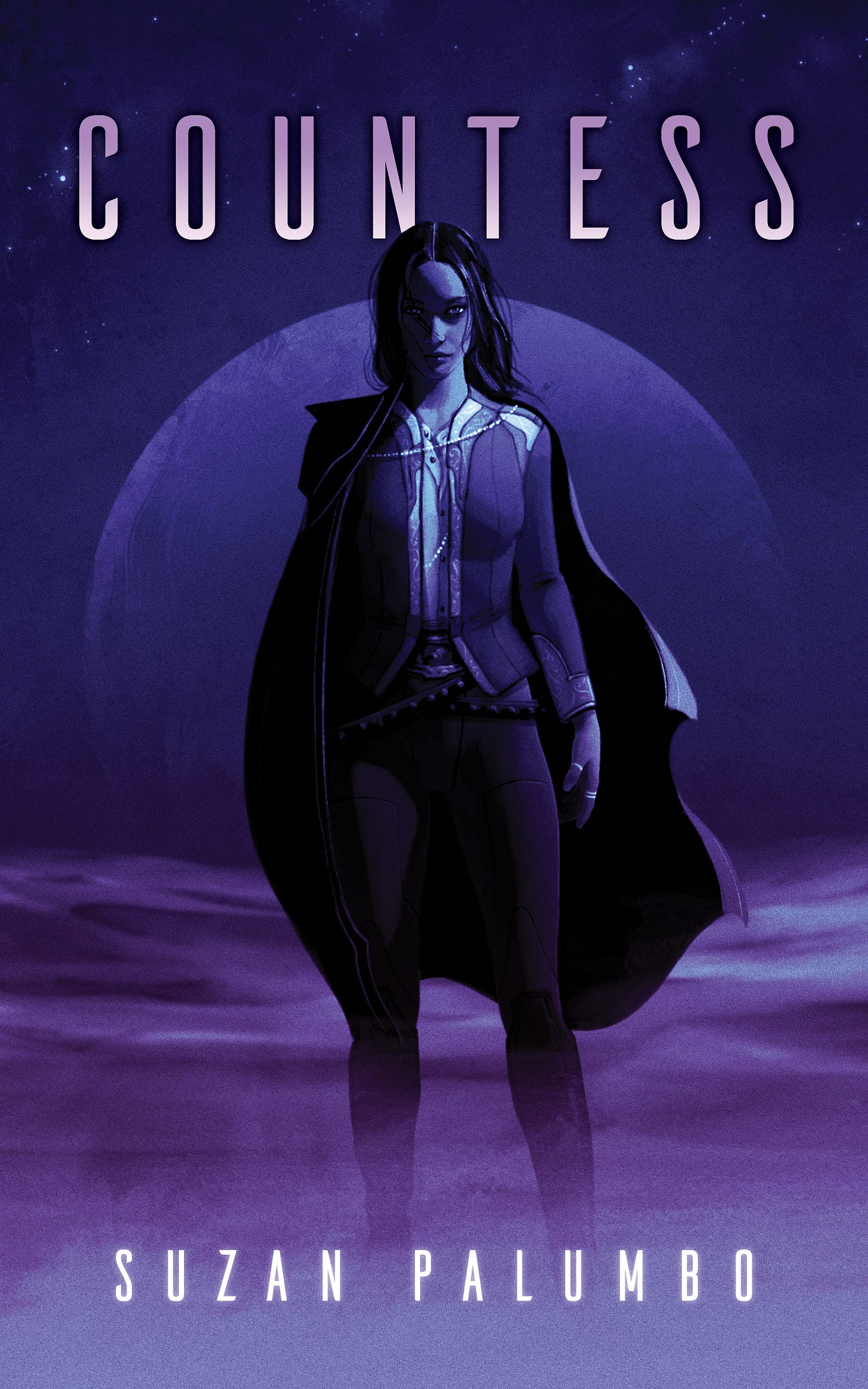

Revolution as a Group Assignment: Review of Countess by Suzan Palumbo

Packing a life-spanning saga into a 200-page novella.

Published: September 2024, ECW Press

Genre: Science Fiction / Action & Adventure

Summary: Virika Sameroo lives in colonized space under the Æerbot Empire, much like her ancestors before her in the British West Indies. After years of working hard to rise through the ranks of the empire’s merchant marine, she’s finally become first lieutenant on an interstellar cargo vessel.

When her captain dies under suspicious circumstances, Virika is arrested for murder and charged with treason despite her lifelong loyalty to the empire. Her conviction and subsequent imprisonment set her on a path to justice, determined to take down the evil empire that wronged her, all while the fate of her people hangs in the balance.

This review contains spoilers for Countess. Thank you to ECW Press & Indie Book Social at TIFA 2024 for a free copy of this book.

While Earth’s richest (and most stupid) billionaires market space as the New Frontier (read: new land to colonize), where humanity might finally shed our old grievances and come together to create a post-racial / post-prejudice / post-scarcity / post-any-problem-at-all world, any reader of science fiction (or, indeed, anyone who ever looked up and looked around at this increasingly horrific world we live in) should understand this: Under the yoke of colonialism and capitalism, a new world will not only create new problems—it’ll also amplify the old ones.

In Countess, Lieutenant Virika Sameroo—an Exterran Antillean immigrant, whose ancestry traces back to those oppressed, enslaved, and/or indentured by British colonizers in the West Indies—is a perfect soldier, giving up her culture, her past, and her life to serve the Æcerbot Empire. But when she’s falsely accused of murdering a superior officer and sentenced to life without parole in a prison pit planet, Virika realizes that no amount of loyalty or deference could earn her respect and dignity in the eyes of her oppressors, and vows to pursue both vengeance and justice through revolution.

Spanning across more than a decade of Virika’s life, Countess packs a punch in just under 200 pages. The fast pacing is as brutal as the actions of the Æcerbot Empire, but Palumbo has masterful control over time: speeding deliriously fast to disorient both Virika and us readers when needed, but slowing down to linger on certain details—a mother’s cooking, a lover’s sweet nothings, a heartbreaking sequence in prison where Virika struggles to cling to sanity through sketching her memories with a sharpened rock—to ground the stakes in tangible emotions.

I was delighted by the motif of food—spices, curries, mouth-watering descriptions that made my stomach rumble—as a vehicle for cultural connection. (It’s not just grey goop or blue milk in this future!) An immigrant to an empire that demands absolute loyalty, punishing those that hold any connection (religious, cultural, spiritual, or political) to their homeworld, Virika finds the strongest link to her heritage through her mother’s cooking. In prison, the first hint of camaraderie between Virika and Kalima, her Antillean prison guard, occurs when Kalima serves her familiar flavours and fruits—food that is not just meant for consumption, but for savouring.

Once Virika escapes prison and gathers resources for revenge/revolution, the book widens its perspective to look at the grand scope of intergalactic conflicts. The violence of the Empire comes in many forms; the bloody physical confrontation at the end of the book is a brutal betrayal, but equally visceral are the decades of verbal, psychological, and mental abuse that precedes it. The victories of the revolution, on the other hand, are less absolute and more Pyrrhic, with no personal glory for the key players, unless and until they’re martyred.

It’s in this second half where I wish the book was just a couple of chapters longer, just so it has the breathing room to slow down and explore the nitty gritty logistical, ideological, and political differences within a revolution. In particular, I find myself wanting an even closer look at the relationship between Virika and her new lover, Dominique, the latter of whom is intimately connected to a piece of Antillean revolutionary history that the former was cruelly divorced from. Virika and Dominique’s unity in cause despite their vastly different upbringings is vital to the central theme of solidarity, especially as it stands in contrast to the obvious disconnections between Virika and her previous romantic interest, an Æcerbot-born trade ambassador.

In Countess, the titular character is no one-woman army, and the revolution is not made-for-TV sensational, all blood and guts and laser sword fights (though the spaceship-chase scene post–prison break is a highlight). But Virika’s story has an undeniably important message: Revolution is a group assignment. A single fracture in the group might render the whole operation moot, but social change—or at least an attempt at it—can only happen when people stand together.